華雪さん(書家)

新潟の地方紙「新潟日報」を貼り込んだ屏風に、滞在制作をしながら新潟で過ごす日々を「日」という文字に込めて書き重ねた作品の前で。

書家としての作品制作のみならず、展示やパフォーマンス、ワークショップ、書籍の題字、エッセイの執筆など、場を限定しない自由な発想で表現を続ける華雪さん。個性豊かな独自のスタイルにつながるヒントは、華雪さんが過ごす丁寧な暮らしのなかにありました。

華雪さんと書の出会い

華雪さんが書道をはじめたのは5歳の頃。きっかけは当時、左利きだった妹さんを右利きに直すため、書道教室に通わせようとした母・秀子さんに頼まれた付き添いだった。しかし、実際に書道の世界に引き込まれていったのは、華雪さんのほうだった。のちに母のように慕う玉記久美子先生との出会いが、ここで訪れる。 玉記先生の教えは実に創造性に富んでいた。書道教室に着くと、例えば新しく習った漢字を訊かれる。すると先生は、字典でその漢字の象形文字を見せながら成り立ちを教えてくれた。絵が好きだった華雪さんにとって、記号のようでありながら、かたちそのものに成り立ちや意味がある漢字は、絵を描くよりもいろいろな想像がふくらむものに思えたという。先生と出会い、教えを受けることで、華雪さんは字を書くことにすっかり魅せられていった。 週に1度のペースで通っていた教室では、その日の稽古が終わったあとに、今週あったおもしろいことをひとつの言葉やひとつの漢字に表して半紙に書いてみる時間があった。華雪さんはこの時間がたのしみで仕方がなかったそうだ。 「今週は何があったっけ?と思い出しながら、その出来事と字をつなげようと考え、書いてみます。でも、なんとなく書いた字は、なんでこの字を書いたの?と先生に訊かれても、うまくつながりを答えられない。『字は言葉。字を書くということは、その字の意味と自分の気持ちを結びつけて書くこと』と、書で字を書くことへの向き合い方を教えてくれたのが玉記先生でした」 この頃、先生に見せてもらった写真がいまでも忘れられない、と語る華雪さん。一字書と呼ばれる、漢字一文字を書く作品で知られる書家・井上有一のポートレートだ。 「その日の書き損じを小脇に抱え、庭に燃やしにいこうとする坊主頭に着流しの後ろ姿でした。なんともいえない迫力を感じて、子ども心にびっくりしたんです。字を書いて表現することに、必死に思いを込めていることが伝わってくるような気がして」 教室にあった井上有一の作品集を開くと、床にひろげた大きな紙に全身をつかって筆を打ち下ろすように書く彼の写真があった。そこに書かれていた字は「花」、「上」、「貧」、「捨」、「不思議」など、まだ幼かった華雪さんにもわかる平易で身近なものばかりだった。稽古に飽きると彼の書によく見入っていたそうだ。こうして、自分自身の生活から湧き出す感情を見つめて、自分のいまを書く「書家」という職業を、初めて意識するようになる。 中学校に上がった頃、10人ほど通っていた生徒が書道教室を辞めるタイミングが重なり、たまたま先生と華雪さんとの個人稽古になった。すると先生から「もっと専門的に勉強してみる?」と提案があり、中国の古典を手本に字を習う稽古をはじめる。技術を学ぶ傍ら、いまにつながる創作も行うようになった。 大学では心理学を専攻したが、20歳まで玉記先生の稽古に通い続けながら、ギャラリーなどで毎年展示を重ねていった。就職活動の時期に入っても、書を続けたいという思いは消えず、そのことを母の秀子さんに話すと、「書を続けたいなら、どんなことでもいいから書家としての仕事をとってきなさい」という条件を告げられる。 そんなとき、個展を見に来てくれた編集者が、茶道雑誌の扉用に、茶室に掛けられる掛軸に書かれた季節の言葉を篆刻で表現する仕事をしてみないかと声をかけてくれた。むろん、扉絵の仕事だけで生活は成り立たないが、「約束は約束だから」と、秀子さんも書を続けることを認めてくれた。当時、ある年配の日本画家の方から、女性が流派に属さず書をやっていくことの大変さを聞かされ、悔しい思いもしていた華雪さん。 「あのとき一言もなぐさめてくれなかったよねって、そのときのことを母に話すと、『そんなに簡単に続けられるほどやさしい世界ではないし、人に言われて諦めるくらいならやめればいいと思っていたのよ。その画家の方が、わたしが言いにくい、きついことを言ってくれたとさえ思っていたから』と笑いながら母は言っていました。書を続けるのに条件を出したのも、娘の覚悟がどれほどのものなのかを確かめておきたい思いからで、母のひと言がなければ、書を仕事にしようと真剣に思えなかったかもしれません」と、振り返る。

同じく、さまざまな「日」の前で。

作品づくりにつながる、いまの自分を知る作業

作品づくりのテーマをいつもどのように決めているのか訊ねてみると、小さい頃からやっていることは変わらず、身の周りを見渡して、日々、気づいたことをノートに書き留めることからはじめるという。 現在、エッセイを書く機会も多い華雪さんだが、文章を書くことは作品づくりにも欠かせない。作品を発表するときには必ず、その字の意味、成り立ちを添えてきた。大学を卒業して、アルバイトをしながら制作をはじめた頃、高校時代から作品を見てくれていた編集者から、作品解説として添えていた字の意味に、自分の身近なことも加えて少し長く書いてみたらと勧められ、作品解説の延長で文章を書きはじめた。華雪さんにとって、書と文章を書くことはどう違うのだろうか? 「文章を書くことは最後の仕上げまで頭のなかで整えながら言葉を引き出していくので、とても難しい作業です。それでも文章を書くのは、書では身体の動きが先に立ってどうしてもこぼれ落ちてしまうような細かな心境の変化を確かめられるからだと思います」 そうした作品づくりの礎となっているのは自分を観察することだという。 「普段暮らしていて、心動かされる何かに気づくことができる自分でいられるように、自分自身のコンディションを確かめようとすることが、自分のいまの思いを確認する作業にもなって、それが字を書くことにもつながっているのだと思います」 身の周りの出来事を濾(こ)して、確かめる作業をすることで、華雪さんは「いま何を書きたいのか?」にピントを合わせようとする。華雪さんのなかにあるアンテナはとても敏感だが、そこから自分のなかに残すものを選びとるための「濾し器の目」は、極めて微細なのかもしれない。ともすれば見過ごしてしまうほどたくさんのことが起こる1日のなかで、暮らしに潜む出来事を注視して、自分のリズムをつくり出すのに、料理が一役かってくれるという。 華雪さんにとって、毎日の食事はいまの自分を知るためのよいバロメーターだ。 「その日食べたい味や食感はどんなものなのか?それを確かめ、つくって食べてみる。想像とぴったり重なるときもあれば、ちょっとずれるときもあるし、毎日のことだからうまくいくときもいかないときも、それはそれだと飲み込める。これだと思ってつくったものを口にしたときは、身体にしっくりきて安心します。一方、忙しい時期や、大勢で話しながら食事をする場面や、何を食べているのか意識できない状況が続くと、頭のなかもごちゃごちゃしはじめるようで、身体がうまく動かなくなってきたりします」 つまり、いろいろなものが混ざり合ったものを一度には味わいきれないということなのかもしれない、と華雪さんは言う。それは料理だけでなく、物事を捉えるとき、すべてにおいて言えるのかもしれないと続けた。身体のなかから溢れ出る感情を受け止めてくれる書

書は、華雪さんにとって生きるために食べることと同じくらいあたりまえにあること。どうしてここまで字を書きたいと思うのか、その原動力は「自分自身が驚くような字を書きたい」という衝動なのかもしれないと話す。ここで言う「自分自身が驚くような字」とは、そのときの自分が表れている字のことだという。 「書き手のいまが、きれいに飾ったものばかりでなく、濁った澱(おり)や、なにもかもを含めて表れていると思えるような字を書きたいんです」 なにか高揚する出来事に出会ったとき、その勢いでものをつくることは大きな原動力になる。けれど、あとからその作品をつくったときの自分を振り返ると、もう少し落ち着けば、違う言葉に置き換わっていたかもしれないと後悔することも多いという。一方で、字を書いてきたからこそ、高揚しやすい自分や、うわべを飾ってしまいがちな自分も知ることができるのだと、華雪さんは続ける。 「そうして考えたり、その考えを捨てたりしながら繰り返し書いているうちに、だんだん高揚の底にある自分が見えてくるときがあるんです」 そんな身体のなかから溢れ出してくる何かを、書は受け止めてくれる存在なのだ。字を書きたい、そのときに生まれてくる感情の根を、床に四つん這いになり、身体全体をつかいながら力を込めて書き、探す。こうして華雪さんの身体性がともなった書のスタイルはできあがった。 現在、『THREE TREE JOURNAL』において『The Sense of Scent 香りの視点』というコンテンツの制作をお願いしている華雪さんに、どのような思いで取り組まれているのかを伺ってみた。 「目に見えず、触れることもできない香りというものをどのように捉えるかは、とても大きなチャレンジです。いままでとは違った見方をしないと自分が書きたいものが見えてこないだろうと思っているので、作品制作をはじめてからの日々は、とても新鮮な毎日です。香りに気を配るようになったことは、自分のなかの変化としてとてもおもしろい。それを言葉にしてどのようにひとに伝えるのかを考える難しさにぶつかり、工夫していくのも新鮮な過程です。暮らしのなかで、香りを通じて心動かされることにどう気づいていったのか、その過程を読者のみなさんにも、いろいろなかたちで感じていただけたらと思います。そしてそれがみなさんの普段の時間を見る新しい視点につながっていけばうれしいです」 このほかに、毎月20日に発刊される集英社の読書情報誌『青春と読書』での書とエッセイの連載や、365日、その日の自分を毎日ひと文字に書き残すというプロジェクトに取り組んでいる華雪さん。自分自身と向き合う日々はこれからも続いていく。

上から、華雪さんが影響を受けた書家・井上有一氏の全文集『書の解放とは』(芸術新聞社)と『生きてい る井上有一』(UNAC TOKYO)の一ベージ、写真家・繰上和美が撮影したポートレート。下の2冊は、華雪さんが書道教室で玉記先生に文字の成り立ちを習った字典、白川静編纂の『字統』(平凡社)と『常用字解』(平凡社)。

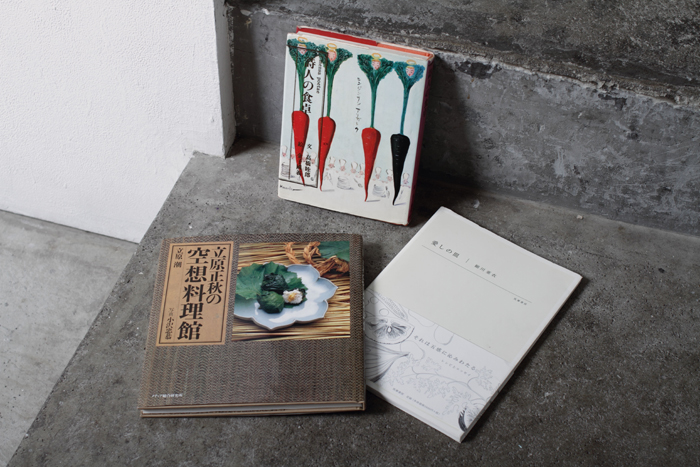

華雪さんにとって、自分をシンプルにしてくれる食べものを教えてくれる料理本3冊。上から右へ順に、文・高橋睦郎、絵・金子國義『詩人の食卓』(平凡社)、細川亜衣著『愛しの皿』(筑摩書房)、文・立原潮、写真・小沢忠恭『立原正秋の空想料理館』(メディア総合研究所)。

左から順に、華雪さんが10歳の時に自身で彫った篆刻「華雪」。毎日使っている小回りが利いて書き心地のいい2本の「一番身近な細筆」。くじゃくの羽を束ねてつくられた「くじゃくの筆」。小学生の頃、華雪さんの髪の毛でつくった「体毛筆」。濡れると自身の髪の毛と同じクセが出るそう。『THREE TREE JOURNAL』トップページのスライドバナーの「丁」の字を書いた「ペンキ用の刷毛」。「日」の屏風の制作でつかった「日本画用の刷毛」。

<クレジット>

PHOTOGRAPHS BY YUKI HOSHINO

SHOOTING LOCATION AT hiromiyoshii roppongi

華雪さんの連載コンテンツ > A Sense of Scent 香りの視点

- Guest File #03

- “Calligraphy is indispensable to me to be able to confirm who I am now.” Ms. Kasetsu (Calligrapher)

- THURSDAY, 20st JUNE, 2013

Ms. Kasetsu's encounter with Calligraphy

Ms. Kasetsu started calligraphy at the age of 5. She was asked by her mother, Hideko, to chaperone her left-handed older sister, whom she was trying to make right-handed by making her go to a calligraphy class at the time. However, it was actually Ms. Kasetsu who would be attracted to the calligraphy world. Here she would meet Professor Kumiko Tamaki, whom she would later look up to as a mother figure. Professor Tamaki's teachings were actually abundant with creativity. For example, whenever Ms. Kasetsu would arrive at calligraphy class, Professor Tamaki would ask her what Kanji she had just learned. Then she would teach her the development of the Kanji while showing her its pictographic form in the dictionary. For Ms. Kasetsu, who loved pictures, Kanji that were like a glyph but had meaning and developments, through which she felt she could expand her imagination more than with pictures. By meeting her teacher and taking her classes, Ms. Kasetsu became completely mesmerized in writing Kanji. In the class, which she attended once a week, when the lesson was over, they had time to write on hanshi (Japanese paper for writing calligraphy) in one Kanji or one word anything interesting that happened that week. Ms. Kasetsu loved this time the most. “I would think, 'what happened this week?' and try writing it, trying to connect the Kanji to the event. However, if the teacher asked me why I wrote the Kanji I somehow wrote, I couldn't explain its link very well. Professor Tamaki taught me how to come to face to face with writing Kanji in calligraphy, explaining, 'Kanji are words. Writing Kanji means attaching your feelings to the meaning of the Kanji.'” Ms. Kasetsu says she will never forget the picture she had her teacher show her at the time. It was a portrait of Yuichi Inoue, calligrapher known for his works in which he writes one Kanji, called Ichijigaki. “It was the backside of his shaved head in deshabille, holding his mistake writings from that day under his arm and trying to burn them in his garden. I was surprised, feeling an indescribable vigorousness. I felt that in expressing himself in writing Kanji, he was frantically communicating to me what he was thinking.” Whenever I opened the collection of Yuichi Inoue's works in the class, there was a photograph of him writing like he was using his whole body to bring his brush down to the large paper spread out on the floor. The Kanji written there, such as “flower”(hana), “above”(ue), “poverty”(hin), “throw away”(sha), “strange” (fushigi), were just simple and familiar things that the still young Ms. Kasetsu could understand. Whenever she was bored of the lessons, she would often stare at his writings. In this way she looked into her feelings boiling up from her life and became conscious for the first time of the profession of 'calligraphy' that is writing a present to herself. When she entered middle school, the timing for about 10 students who quit the class overlapped, and occasionally the lessons became personal lessons with her and the teacher. The teacher then planned more specialized lessons, starting to give lessons with characters sampled from old Chinese dictionaries. Besides learning the skills, she also began creating works that linked her to her work now. In University she majored in Psychology, but up to 20 years of age she would overlap exhibitions every year at galleries with attending Professor Tamaki's lessons. Even once she started looking for work, she desired to continue doing calligraphy. When she told her mother, Hideko, she responded with one condition: “If you wish to continue doing calligraphy, get a job as a calligrapher.” It was then that an editor who had come to see her personal exhibition asked her to work expressing herself in engraving seasonal words written on scrolls hung in tea rooms on the covers of tea ceremony magazines. She obviously couldn't live off of work making cover scroll paintings, but Hideko encouraged her to continue calligraphy, saying “a promise is a promise.”At that time an older Japanese painter had told her of the troubles of continuing to write calligraphy without being hired by a school. She began to feel frustrated. “When I told my mother that, that he hadn't given me any comforting words, she smiled at me and said, “The world isn't such a kind place that you can continue on that easily, and if you really feel like quitting from what people tell you, then I think you should quit. I think the painter even told you what was hard for me to tell you.” From her desire to confirm how prepared her daughter was, and having put out a condition for me to continue calligraphy, I might not have seriously tried to become a calligrapher if it weren't for her words,” she says, looking back.The work of getting to know herself, connecting to her creating works.

We asked her how she always decides the topics of her works. She told us that she takes notes of the things she notices around her every day, just as she had always done since she was a child. Ms. Kasetsu currently has many chances to write essays, and the writings are essential to her works. When she presents her works, she always attaches the Kanji's meaning and development. When she graduated college and started making her works while working part-time, the editor who had come to see her works since she was in high school suggested that she try writing slightly longer, adding the things near to her heart in the meaning attached to the Kanji as an explanation of the work. She began writing extended versions of the explanations of her work. How different is doing calligraphy from writing essays for Ms. Kasetsu? “I'm always checking the words while putting the final work together in my head when writing essays, so it's very tough work. Even so I think it's because writing essays can confirm the small changes of heart that come out anyway because the physical movements precede them in calligraphy.” What's become her foundation for such works is her examining herself. “I think that checking my own condition so that I can be someone who can notice what inspires me in my daily life has also become a work of examining my current thoughts and that connects to the characters that I write.” By doing the work of checking by straining the events around her, Ms. Kasetsu tries to bring in to focus what it is she wants to do at the time. Her antenna is very sensitive, so her “eye filter”to take what's left in her from that may be highly refined. In a day where so many things occur that she may overlook them, she watches for the events hidden in her life, and in order to create her own rhythm, cooking is important to her. For Ms. Kasetsu, her meals every day are a good barometer to understand herself. “I check what flavors and textures I want to eat that day, make them and try eating them. There are times where it's exactly as I had imagined it, and other times where it's a bit off, but because it's a daily thing, I can swallow both the times it goes well and the times it doesn't as they are. When I think, “this is it!”after tasting it, I'm at peace with my body and relax. On the other hand, when I'm busy or in places where I eat while talking with many people or if I'm situations where I can't concentrate on what I'm eating, my mind starts to get mixed up and my body doesn't move very well.” Ms. Kasetsu says, in other words, it might mean that she cannot taste many things mixed together at once. She continues that it could be said of all things when she takes them up, not just cooking.Calligraphy takes her overflowing feelings from inside her body

Calligraphy is something as obvious as eating to live for Ms. Kasetsu. She says that that drive, why she needs to write Kanji that much, might be the drive “to write Kanji that even surprise me”. This “Kanji that surprise me” refers to Kanji that reflect herself at the time. “Everything I've written now isn't just things that can be beautifully displayed. I want to write characters that express everything, even dirty filth.” When she has any uplifting events, making things with that power is a big drive. However, whenever it's a little quieter and she looks back at herself at the time of making the work there are many times when she feels regret and wishes that she had written the words differently. On the other hand, because she's been writing characters, she explains that she can get to know that there are times she is easily uplifted or tends to color her projects. “There are times that when I'm rewriting while thinking or getting rid of ideas, I gradually start to see myself in the bottom of this emotional elevation.” Calligraphy is that something that takes the something that overflows from inside her. It searches for the root of her feelings born in the moment of wanting to write the character while crawling on all fours and using her entire body and writing with her power. This is how Ms. Kasetsu's made her style. We asked Ms. Kasetsu, who is currently creating contents for “The Sense of Scent”on “THREE TREE JOURNAL”, how she approaches the project. “How to capture intangible and invisible scents is a big challenge. I don't think I can envision what I want to write unless I change the way I've viewed things up to now, so every day after I've started making the project have been very fresh days. Having become mindful of scents is very interesting as something inside of me. I run into the challenge of thinking about how to turn it into words and express it to people and inventing is also a fresh process. I want every reader to feel in many different ways the process, how I realized I was inspired by scents in my daily life. I would be happy if it led them to a new way of viewing their everyday lives.” Ms. Kasetsu is also working on a project where she writes one words about her every day for 365 days and serial essays and calligraphy in “Seishun To Dokusho”, an informational reader's magazine published by Shueisha every month on the 20th. She will continue to come face to face with herself every day.<Captions>

Photograph (above)

In front of a work with the character “hi”(日) written to express her every day while staying in Niigata for work on a folding screen with the local newspaper “Niigata Nippō” attached to it.

Photograph (Middle)

The same, before many “hi”(日).

Photograph (Below)

Ms. Kasetsu and her green books and tools.

(1st) From the top, the portrait and Mr. Yuichi Inoue's collection “Sho no Kaiho to wa” that influenced Ms. Kasetsu. The bottom two volumes are “Jōyō Jikai”and “Jitō”compiled by Shizuka Shirakawa, the Kanji dictionaries from which she learned the development of the characters in Professor Tamaki's calligraphy class.

(2nd) Three cook books that have taught Ms. Kasetsu foods to simplify herself. From top to right, “Shijin No Shokutaku--mensa poetae” text by Mutsuo Takahashi and illustrations by Kuniyoshi Kaneko; “Itoshi No Sara”by Ai Hosokawa; and “Tachihara Masaaki No Kūsōryōrikan”text by (U)shio Tachihara and photography by Tadayuki Ozawa.

(3rd) From left, the engraved seal “Kasetsu”that she made when she was 10. Her two “nearest to her heart fine brushes” that she uses every day are comfortable to write with and easy to use. Her “peacock brush” made of peacock feathers tied together. Her “hair brush”made of her hair when she was in elementary school. Her hair when wet is the same way, she says. The “paint brush” she wrote the character “chō”for the THREE TREE JOURNAL top slide banner with. The “Japanese paint brush” she used in her folding screen work with “hi”(日).

<Credits>

PHOTOGRAPHS BY YUKI HOSHINO

SHOOTING LOCATION AT hiromiyoshii roppongi

Ms. Kasetsu's Serial Contents >A Sense of Scent 香りの視点